Spontaneous remission of cancer is defined as the remission of cancer without any treatment, or with treatment that would not be expected to cause a tumor to decrease as much as it does. Spontaneous remission may be partial or complete and may be temporary or permanent.

Also known as “St. Peregrine’s tumor,” cancer has been noted to sometimes mysteriously disappear for centuries.1 Peregrine Laziozi was a 13th-century priest with cancer (possibly a bone tumor of his tibia) whose cancer disappeared after he was scheduled for an amputation of the leg containing the tumor. The cancer was gone—there was no sign of the tumor.

Certainly, a misdiagnosis may have been made in the 13th century, but in the 21st century, we have indisputable evidence that spontaneous resolution does sometimes occur.

How Often It Happens

Though we have clearly documented cases of spontaneous regression, it’s hard to know how common this phenomenon actually is. We know it is not rare, with over a thousand case studies in the literature. In addition to those studies which document a cancer which goes away without any treatment, it’s not clear how often a cancer make go away despite treatment or at least decrease in size despite treatment.

Some have estimated the incidence to be roughly one out of 100,000 people,1 but it’s difficult to know if that number is even in the ballpark. It does appear to be more common with some tumors rather than others, with spontaneous regression of blood-related cancers such as lymphoma, and skin cancers such as melanoma being reported more commonly.

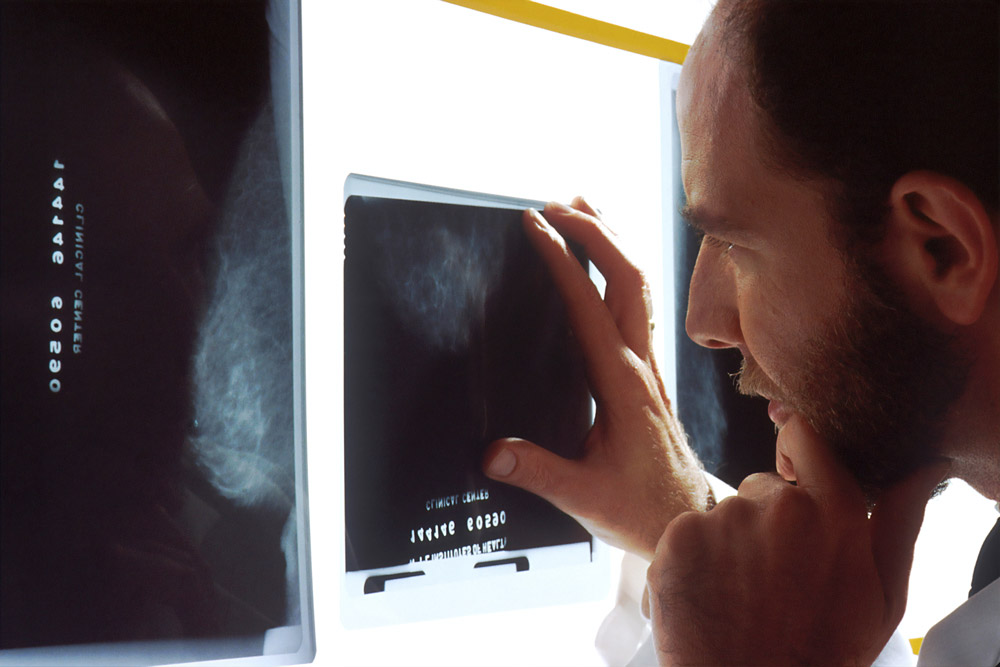

While most studies of spontaneous remission look back in time trying to determine why a cancer simply went away, a 2008 prospective study suggested that spontaneous remission is much more common than we think. In this study looking at screening mammography, it was found that some invasive breast cancers detected by mammogram spontaneously regress. This study published in the Archives of Internal Medicine estimated that 22% of invasive breast cancers went away without treatment.2 Since these tumors were asymptomatic—women did not feel a lump—they would not have had any way of knowing that they had invasive cancer without screening. Since there are many cancers that we do not have screening methods for, it could be that early invasive cancer occurs—and goes away before diagnosis—much more often than we think.

Causes

We’re not entirely sure what the molecular basis is that lies beneath the spontaneous regression of cancer. Theories have been cited which have spanned the spectrum from spiritual reasons to immune causes. That said, an immunologic basis could certainly make sense.

Infection and the Immune System

Looking at people who have had a spontaneous remission of their cancers, it’s quickly noted that most of these regressions are associated with an acute infection. Infections often result in a fever and stimulation of the immune system.

We know that our immune systems have the ability to fight off cancer. That is, in fact, the logic behind immunotherapy. Immunotherapy medications, while still in their infancy, have resulted in dramatic remissions of cancer for some people, even in the advanced stages of cancer. These drugs work in different ways, but a common theme is that they essentially enhance the ability of our own immune systems to fight cancer.

Infections which have been associated with spontaneous remission3 include diphtheria, measles, hepatitis, gonorrhea, malaria, smallpox, syphilis, and tuberculosis.

A Case Report

A 2010 report in Surgery Today brought up what others have found in the past, and what is well documented as a spontaneous remission from lung cancer.4

A 69-year-old woman was found to have lung adenocarcinoma, a form of non-small cell lung cancer. Her cancer had spread to her adrenal glands—adrenal metastases—and therefore, was labeled as stage IV non-small cell lung cancer. Stage IV lung cancer is the most severe stage of the disease with the poorest survival rate.

One month following her diagnosis, and before she had any treatment, both the tumor in her lung and the metastasis to her adrenal gland had shrunk considerably on both a CT scan and a PET scan. (A PET scan is an imaging test which uses radioactive glucose, and allows physicians to get a more accurate assessment of tumor activity than on a CT or MRI alone.) She then underwent surgery for lung cancer and was doing well 14 months later.

Lessons to Learn From Spontaneous Remission

Certainly, spontaneous remission is uncommon, and it would be casting false hope to spend too much time considering this possibility. Yet talking about the uncommon finding of spontaneous remission emphasizes something important for everyone living with cancer.

People Are Not Statistics

Statistics are numbers. They tell us how the “average” person did in the past during treatment. They are less reliable at predicting how any one single person will do, or how anyone will respond now that newer and better treatments are available. As our understanding of cancer increases, we also now recognize that no two cancers are alike. Even though two cancers may be of the same cell type and same stage, and even look identical under the microscope, they may be very different on a molecular level. It is at the molecular level, however, that the behavior of a tumor originates, and will dictate the response to treatment and ultimately prognosis.

The Study of Exceptional Patients or “Outliers” is Important

In the past, people who survived cancer despite the odds being against them were often dismissed as being an anomaly or an exception. Medicine has shifted 180 degrees yet again to acknowledge that outliers should be closely examined rather than dismissed. This approach has been confirmed as the mechanism of growth of cancer is better understood. An example is the use of EGFR inhibitors in lung cancer.5 When first available, it’s wasn’t known why these drugs worked, but they were considered fair to poor drugs as they only worked on around 15 percent of people with the disease. Now we know that they work on people who have EGFR mutations in their tumor. When the drugs are given only to people who test positive for the mutation, the majority of people respond (and those who don’t have the mutation aren’t subjected to a treatment that will be ineffective).

Taking a look at some of the characteristics of “exceptional patients” with cancer may give us some clues about how to raise our odds as well.

This article and material was written by Lynne Eldridge, MD and was originally published on his blog at www.verywellhealth.com on March 18, 2021

If you like this post you will also enjoy:

- Imagery Can Help You Recover from Injuries and Illness – Learn Mind Power With John Kehoe.

- Mind Power and Belief for Recovery and Healing.

- How Athletes Recover Quicker Using Mind Power.

- The Healing Power of Illness Book Overview.

Further Reading: